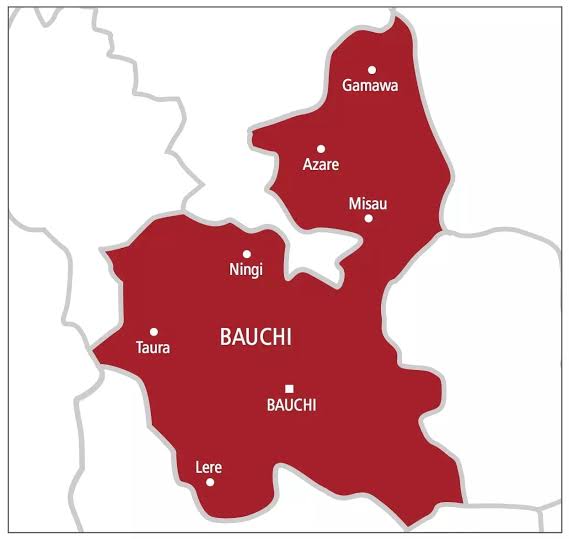

News Investigators/ No fewer than 37 condemned prisoners are awaiting execution after being sentenced for capital crimes in Bauchi State.

Ahmed Tata, the Public Relations Officer (PRO), Nigerian Correctional Service (NCoS), Bauchi State Command, said this in an interview with the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN), on Tuesday in Bauchi.

Reacting to a NAN survey on why the state governors are reluctant to sign death warrant, Tata said the condemned prisoners comprised 36 males and one female.

He recalled that none of the democratically elected governors in the state had signed death warrants since 1999.

The spokesman, however, said that governors during the military might have signed death warrants for those on death row.

A legal luminary, Jubrin S. Jubrin, urged the state governors in the country to expedite signing the death warrant of condemned prisoners to ensure justice.

Mr Jubrin said the actions of the governors might be connected to the dismal number of the condemned prisoners in the country.

“The governors have a duty to make sure that once the court has sentenced somebody to death and he exhausted the chances of appeal, the sentence should be executed.

“Although, signing of death warrant also depends on a particular state depending on its geographical location and culture, it might be the factors on how these responsibilities are to be handled.

“Secondly, the role of the office of the Attorney General as the chief law officer of a state, each of the Attorney General has a binding duty to offer legal advice on all legal matters including the exercise of the power to sign death warrants by the governors.

“We need to know are they very many? If there are many, probably, it would have raised a concern as to why are we keeping as much as the number of people awaiting execution?

“Why not just forgive them if the governor wants to or if he is committing to the execution, it should be done once and for all,” he said.

Mr Garba Jinjiri, Chairman, Network for Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in Bauchi, highlighted that irreversibility of execution was one of the reasons behind the governors’ reluctance to sign the death warrant.

“What I mean here is that if a mistake is later discovered, like a wrongful conviction, it cannot be corrected after execution.

“Also, some convicts may still have cases under appeal or awaiting decisions from higher courts.

“I also want to believe that some governors personally believe in the sanctity of life or oppose capital punishment on ethical grounds,” he said.

According to him, executions could spark protests or criticism from human rights groups, academia and the public.

The governors, he said, might avoid signing the death warrant to prevent alienating voters or interest groups.

Also, Dr Muhammad Reza, a Jigawa-based political analyst, highlighted that democratic constitution indirectly impeded the implementation of capital punishment in Nigeria.

He said the constitution vested the authority to approve executions in the hands of the governor and the president.

Reza said the governors consistently withheld such approval primarily to avoid antagonising foreign donors, who might judge them based on human rights standards, and withdraw their support.

“What they fail to realise is that this reluctance has contributed to a steady rise in criminality across the country since 1999. There is a growing argument that justice should be proportional, just tit for tat,” he said.

Reza, however, called for a review of capital punishment in the country.

Another lawyer, Hassan Muhammed said the Nigerian constitution and legal system empowered governors with the final power to authorise execution of capital punishment, but it has been impeded due to a variety of legal, ethical, political and procedural considerations.

According to Muhammad, Section 212 of the 1999 Constitution, gives the governors prerogative of mercy, enabling them to grant a pardon, substitute a lesser punishment, or affirm a death sentence.

“This means a governor must personally approve the execution of a condemned inmate thus placing a heavy legal and moral responsibility on the individual, often deterring them from exercising their powers.

“Nigeria’s legal system is often criticised for delays, weak investigation procedures, and lack of access to quality legal representations and wrongful convictions are indeed a real risk.

“Executing someone whose conviction might later be overturned, poses serious legal and human rights implications since Nigeria is a signatory to several international human rights treaties,” he said.

In the same vein, Yusuf Abubakar, attributed the governors’ actions to the growing campaign against capital punishment by human rights and development organisations in spite of its legality in Nigeria.

Abubakar said that signing a death warrant was politically sensitive as the governors might face public backlash or protests from human rights groups, religious bodies, or political opponents.

He said that many governors avoided such decisions during their terms in office thereby leaving the condemned prisoners in a legal limbo.

“Nigeria is a deeply religious country and both Christianity and Islam emphasise mercy and forgiveness, thus personal beliefs of a governor often play a role in making such decisions.

“A governor who is morally or religiously opposed to capital punishment may decline to sign death warrants, regardless of the law,” he revealed.

While capital punishment remained legally valid under Nigerian laws, Abubakar said that the governors’ reluctance to sign death warrants reflected a complex legal caution, moral reservation, political calculation, and procedural dysfunction.

He said these factors created a de facto moratorium on execution, resulting in thousands of condemned inmates languishing in limbo.

NAN